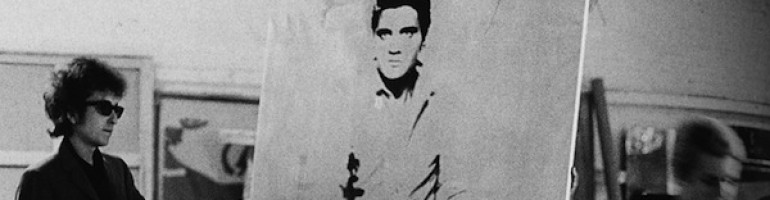

Bob Dylan appears to have been undergoing a kind of prolonged death and rebirth initiation throughout the mid-sixties, similar to those experienced by shamans in numerous cultures around the world, which seems to have allowed him to act as a catalyst for the transformation of his culture. According to folksinger David Cohen: “his power, his mystique, just affected people in crazy ways,” many in his audience sensing that “this guy knows, this guy feels, and you want to be with him.” Or as Eric Andersen put it: “He’s got the heaviest vibes I’ve ever felt on anyone,” apparently a common perception by those who knew Dylan. By the mid-sixties, Dylan seems to have developed his intrinsic ability to embody the affective quality of the moment to such a high degree that he became the center of “a magnetic field” for people’s deepest desires and aspirations, similar to Elvis Presley’s role in his cultural moment, but at a more complex order of magnitude.[i]

Concluding the section about his self-naming in Chronicles, Dylan writes:

As far as Bobby Zimmerman goes, I’m going to give this to you right straight and you can check it out. One of the early presidents of the San Bernardino Angels was Bobby Zimmerman, and he was killed in 1964 on the Bass Lake run. The muffler fell off his bike, he made a U-turn to retrieve it in front of the pack and was instantly killed. That person is gone. That was the end of him. [ii]

What Dylan seems to be implying is that the fact that there was another man named Bobby Zimmerman who died in a motorcycle wreck in 1964 (actually 1961, though this discrepancy does not seem negatively to affect Dylan’s point) is a meaningful coincidence (the definition of Jungian synchronicity) that symbolically mirrored and enacted the death of Dylan’s old identity. This is an idea the validity of which it would be impossible for a purely materialist mode of thought to accept, at least outside of a novel or a film, but Dylan believes that the world does indeed work in mysterious ways. The name coincidence combined with the manner of the other Zimmerman’s death, which pre-iterates one of the primary images in Dylan’s mythology, the motorcycle crash of 1966, seems to suggest to Dylan a kind of cosmic orchestration in which events are somehow pulled into his wake of significance.

In his 2012 Rolling Stone interview, Dylan expands on the subject of the two Bobby Zimmermans, declaring: “You know what this is called? It’s called transfiguration. Have you ever heard of it?” “Yes,” the interviewer responds. “Well, you’re looking at somebody,” Dylan declares. “That . . . has been transfigured?” comes the hesitant rejoinder. “Yeah, absolutely,” Dylan asserts:

I’m not like you, am I? I’m not like him, either. I’m not like too many others. I’m only like another person who’s been transfigured. How many people like that or like me do you know? . . . Transfiguration: You can go and learn about it from the Catholic Church, you can learn about it in some old mystical books, but it’s a real concept. It’s happened throughout the ages. . . . It’s not like something you can dream up and think. It’s not like conjuring up a reality or like reincarnation – or like when you might think you’re somebody from the past but have no proof. It’s not anything to do with the past or the future. So when you ask some of your questions, you’re asking them to a person who’s long dead. You’re asking them to a person that doesn’t exist. But people make that mistake about me all the time. I’ve lived through a lot. . . . Transfiguration is what allows you to crawl out from under the chaos and fly above it. That’s how I can still do what I do and write the songs I sing and just keep on moving. . . . I couldn’t go back and find Bobby in a million years. Neither could you or anybody else on the face of the Earth. He’s gone. If I could, I would go back. I’d like to go back. At this point in time, I would love to go back and find him, put out my hand. And tell him he’s got a friend. But I can’t. He’s gone. He doesn’t exist. . . . I’d always been different than other people, but this book [about the other Bobby Zimmerman, written by Ralph Barger along with Keith and Kent Zimmerman (who bear no immediately apparent relation to either of the Bobby Zimmermans)] told me why. Like certain people are set apart. . . . I didn’t know who I was before I read the Barger book. [iii]

A 71-year-old Dylan, in a simultaneously more open and more cantankerous mood than usual, declares unequivocally that he was fundamentally transformed in his twenties, that he died and was reborn through something like the Christian process of Transfiguration, the recipient of which becomes spiritually exalted, taking on an aspect of divinity, a process that bears a striking similarity to the shamanic initiation elucidated by Mircea Eliade and others. The Transfiguration of Christ, which St. Thomas Aquinas referred to as “the greatest miracle,” is when Jesus shined radiantly upon a mountain (perhaps like the Beatles on the Cavern stage) and became mysteriously connected to the Hebrew prophets Elijah and Moses who appeared beside him. In the New Testament, Paul refers to the believers being “changed into the same image” through “beholding as in a glass the glory of the Lord,”[iv] which suggests that the witnessing of the transfigured individual can mediate a similar transformation in those who believe in that Transfiguration, acting as a mirror for the collective. Ultimately, the Transfiguration appears to have been fulfilled in the death and rebirth of Christ, which seems to be a kind of fractal reiteration of the archetypal death and rebirth of the shamanic initiation that Dylan appears to have experienced.

As Dylan asserts, those few who are fundamentally transformed through this kind of process, by various accounts including primal shamans, ancient mythological heroes who traversed the underworld (Osiris, Dionysus, Heracles, Persephone, Orpheus, Psyche, Odysseus, Aeneas, Theseus, Gilgamesh, Odin, and others), figures from the Hebrew Bible (Jacob, Enoch, Elijah, Moses), the New Testament (Mary and Christ), and the Buddha, are reborn as new people, which separates them from the majority of humanity who have not undergone such a transformation. According to Dylan, this Transfiguration is not something that one can “dream up and think” in a hypothetical, conceptual way, but something that one either feels or does not. From Dylan’s perspective, which is very much like that articulated by William James, one cannot choose one’s destiny. Rather, one either knows that one has been transfigured or one does not, and the skepticism of those who have not experienced Transfiguration, either in themselves or in others, has no bearing on the reality of the phenomenon. As it is expressed in several places in the New Testament, “He that hath ears to hear, let him hear.”[v]

Thus, for Dylan, his young self, named Bobby Zimmerman, died during the mid-sixties, culminating in Dylan’s motorcycle crash, which was synchronistically presaged by the death of the other Bobby Zimmerman in a motorcycle crash a few years before, regardless of whether it was 1961 or 1964. However, after the 2012 interview, Rolling Stone was apparently able to determine that the biker Bobby Zimmerman died “within weeks” of Robert Shelton’s 1961 review of Dylan’s show at Gerde’s Folk City in the New York Times, which catapulted Dylan into the limelight, essentially marking the beginning of Dylan’s public career.[vi] In a roundabout way, this chronological mistake in the book from which Dylan took his information only serves to add credence to Dylan’s interpretation, for naratologically speaking, the 1961 date seems even more perfectly orchestrated to confirm Dylan’s conviction of his Transfiguration than 1964. Indeed, the five year period between September 1961 when Dylan was elevated by Shelton’s review and July 1966 when he crashed his motorcycle and went into seclusion is one of the most creative, epochally transformative half-decades that any artist has ever undergone.

Furthermore, by declaring that “it’s not anything to do with the past or the future,” Dylan seems to be evoking something like Bergsonian duration, implying that his Transfiguration is partially constituted in the shift from relating to time as quantitative to understanding that moments with similar archetypal qualities resonate in a qualitative way that seems to exceed linear temporality. Although the two Bobby Zimmermans were materially unconnected, the mode of thought Dylan enacts, which appears coextensive with the generally predominant mode of thought prior to the seventeenth century, sees a closer connection between the young man who would become Dylan and another young man with the same name who had died years before than between Bobby Zimmerman from Hibbing and the famous singer Bob Dylan. As Dylan asserts, he can never go back to being Bobby Zimmerman no matter how much he might want to revisit his former self, for this is apparently the price one must pay for Transfiguration: it is impossible to unknow something once it has been deeply experienced. Or as Heraclitus expressed it: “You cannot step into the same river twice.”

According to Dylan, this shift in perspective has been a primary factor in allowing him to do what he has done, “to crawl out from under the chaos and fly above it,” for in this mode of thought, the chaotic meaninglessness of pure materialism, consisting of atoms randomly colliding for no reason, can be overcome by embracing a view of life as filled with cosmic significance, though hopefully tempered by intellectual rigor. The material facts do not change in this mode of relation, though the results of approaching the world in this way constitute “that slightest change of tone which yet make all the difference,” as Whitehead puts it. In his narrative of the two Bobby Zimmermans, Dylan seems to imply that something like the order of the world sacrificed another man with the same name as him to literalize the death of one of the most transformative figures in history’s original identity. This type of meaningful coincidence occurs frequently in literature and film, but our culture usually assumes that these instances are merely plot devices invented by the author rather than occurrences containing extra-textual meaning. Although there is no mode of causation that has been broadly accepted in the main streams of late modernity which could explain such a phenomenon, the ancient and well-established principles of formal and final causation offer just such an explanatory mode. From this perspective as articulated by Dylan, both the symbolic and literal deaths of the two Bobby Zimmermans are expressions of a formal cause, the sacrificial death and rebirth of the individually embodied shamanic archetype on a mass scale apparently luring culture towards a final cause, a collective Transfiguration at that moment in the mid-sixties.

[This is a (slightly modified) excerpt from my book, How Does It Feel?: Elvis Presley, the Beatles, Bob Dylan, and the Philosophy of Rock and Roll]

[i] Epstein 134.

[ii] Chronicles 79.

[iii] Rolling Stone 2012. The book Dylan is referring to is: Sonny Barger, Keith Zimmerman, and Kent Zimmerman, Hell’s Angel: The Life and Times of Sonny Barger and the Hell’s Angels Motorcycle Club (New York: William Morrow Paperbacks, 2001).

[iv] Holy Bible: King James Version (Nashville, TN: Holman Bible Publishers, 1979) 2 Corinthians 3:18.

[v] The King James Bible, Matthew 11:15.

[vi] “Bob Dylan: His Hells Angel Conversion,” The Guardian Music Blog, http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2012/sep/20/bob-dylan-hells-angel-conversion

Pingback: Bobby Zimmerman | Blog Dylan

Pingback: Bobby Zimmerman 1941-1961 | The Shovel Shop

This is great, thank you for this analysis, just read that interview on monday and got here by searching for a photo of Bobby w/his bike. So great to have found your site, gonna read through it,

Thank you, Daniel. I’m glad you found it interesting. Let me know what you think of the other pieces.

She says, “You can’t repeat the past,”

I say “You can’t? What do you mean you can’t? Of course, you can.”

The big question is… Have YOU looked to see if there is an obituary on the Internet with your name on it? In it are there multiple “connecting things” to your life? If so… Buckle up baby

Hi Jared, It seems to me that this synchronicity is particular to Dylan, but there are many other coincidences occurring all the time if one is open to the qualitative temporality characteristic of formal causation, and if one pays attention to subtle archetypal resonances. The difference with Dylan’s synchronicity is that it was of world-historic significance.

Pingback: T’I ZBRESËSH MOTORIT | | Media e lirë - blog kolektiv shqiptar

Pingback: Murder Most Foul and America’s Soul, Part One – MoreOrthodoxy